Righting the River

August 2010

by Harper Scott Clark

Telegram Staff Writer

Unlike critters, rivers don’t appear on the endangered species list if they get into ecological trouble. They are said to be impaired.

Brad Ware, who owns 2 miles of riverfront on his property in Killeen, stands in the Lampasas River as he picks up some algae that has formed.

In 2008, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality listed the Lampasas River as impaired. Testing showed elevated bacteria concentrations, making it unsuitable for recreational use.

It wasn’t news to the landowners along the winding stretch of the Lampasas. In 2004 a TCEQ report showed a similar finding.

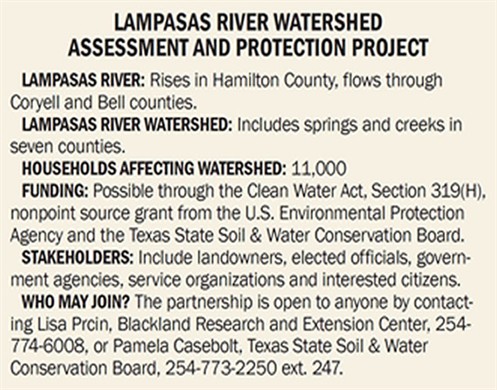

Two major groups have reached out helping hands. The Blackland Research and Extension Center in partnership with the Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board began a project in May 2009 to return water quality. They named it the Lampasas River Watershed Assessment and Protection Plan.

In June of that same year, landowners in the Lampasas valley formed Save the Lampasas River Inc. to protect the fragile river environment. The first is grant funded through the Environmental Protection Agency. The second is a stakeholders association. Many of its members participate in the watershed protection project.

Lisa Prcin, a research assistant at Blackland, said the approach has been one of placing the stakeholders in the Lampasas watershed into the decision-making process. She said a regulatory stance was ruled out. “A watershed protection plan simply asks for their input,” she said. “The key word is voluntary.”

Pamela Casebolt with the Soil and Water Conservation Board said stakeholder groups involved in the project are proactive and knowledgeable. “They’ve lived here a majority of their lives and they truly care about the Lampasas and its quality,” she said. “They have seen the area’s land use change and know it continues to change. They want to insure the quality and beauty.”

Part of that change is urbanization – particularly near Copperas Cove and south Killeen where the river passes from a rural into an urban landscape. What had been 500-acre farms are now subdivisions with high population density.

Prcin said wildlife, livestock, septic systems not up to standard or wastewater treatment plants not operating properly can also cause high bacteria counts in the river. Other pollution comes from fertilizer and chemicals. For farming and ranching, she said some possible solutions are terracing to keep runoff out of the river, installing filter strips, grazing management and using alternative water sources to draw farm animals away from the river.

LAMPASAS STACKHOLDER

Judy Parker, a member of Save the Lampasas, lives on the south bank of the river below Killeen. She also serves on the 19-member steering committee for the Watershed Protection Plan.

“What I see is a lot of erosion,” she said. “Within the last three years for some reason it’s gotten worse. We’ve had a lot of bank failures on the other side of the river on the north side where the river turns.” Parker said she’s talked to many up and down the river and nobody has any answers.

“We’re in Texas Hill Country even though the people in the Hill Country don’t want to include us,” she said. “This is the Balcones Escarpment. When we get heavy rains it goes into flood stage almost immediately.”

As to pollutants, she said she thought many ranchers and farmers have been using methods that diminish runoff of chemicals and livestock waste for a long time. She sees a problem in the many subdivisions that have gobbled up farmland in south Killeen in recent years.

“People are tending their lawns and think the more fertilizer and pesticide you put the faster and better it will grow. What they don’t realize is it can only absorb a certain amount of the nutrients you put on it. The rest washes off into drainage ditches and storm drains into the river.”

She said dog owners are not cleaning up after their pets and that is washing into the river, too. “It’s not that they are doing this on purpose,” she said. “It’s an education issue we need to address.”

FARMER AND RANCHER

Bradley Ware is the fourth generation owner of a 296-acre farm south of Killeen that dates back to 1874. It has two miles of Lampasas riverfront.

“I think it’s a natural progression as a result of population increase,” Ware said. He said he also has an issue with the way some of the tests were run. He said he believes there were cases where scientists took samples from under bridges where hundreds of swallows nested.

“And you don’t go to a still pool so stagnant it will be high in nitrogen and low in oxygen,” he said. “Where the river is running it will be high in oxygen. Where it’s still it will be high in nitrogen.”

But Ware said landowners along the river accept the fact there is a problem and it will only get worse. “We are smart enough as a group to know we should stay together,” Ware said. “No one is trying to point a finger at any one group. It’s a combination of everyone and if everyone would do a little to help we would get the river back up.”

There are solutions, he said. “We can terrace our land,” Ware said. “You see that berm I built there where my field runs along the river? It keeps runoff from spilling into the river.”

He said it’s possible to control wildlife. “Wild hogs will wallow in the river and leave their feces,” he said. “But Texas Parks and Wildlife could authorize a bounty on feral hogs and coyotes and increase the limit on deer.”

Ware held up a handful of green algae from the river’s surface. He said it’s not an indication of pollution per se. “Sunlight makes algae grow. But I’ve seen it so thick you could walk across the river on it. And other times I’ve seen algae kills where it turns black. That could be from a city sewer plant that has dumped chemicals. Or it could be a spill upstream of anhydrous ammonia fertilizer.”

WHERE IT’S HEADED

Prcin said a steering committee meeting in Lampasas on Thursday saw stakeholders agree on data to go into a computer model that will eventually manage the watershed. It included the numbers of feral hogs and other wildlife, livestock and septic systems.

The entire watershed records 11,000 households. She said the early stages of the project were the data gathering and analysis phase. The project is now in the developmental stage networking with stakeholders and getting their input on problems and solutions.

The final stage will be implementation of the final plan, she said. At that point the project can apply for grants.

“Once we have a plan developed we will have a document that is a toolbox of practices to restore water quality,” Prcin said.

Casebolt said the finished document would be a road map for the next 10 years.

–Reprinted with permission of Temple Daily Telegram