Survey crews in the beginning targeted the more populated counties or regions with strong agricultural economies. Bell and surrounding counties were among the earliest studied. The least populated counties, such as sparsely populated areas in West Texas, were the last to be surveyed. The actual “last acre” is on private land between Van Horn and Dell City in Hudspeth County, population 3,115 and located immediately east of El Paso.

“It’s not that those counties weren’t important,” Williamson said. “It’s just that, at the time, the primary land use was not as intensive and the counties were sparsely populated.”

In all cases, soil scientists take general inventories of each county. They contact the landowner for permission to dig samples and map the soil. The scientists take numerous samples because not all soils are alike; one pasture can contain several different soil types.

“Normally you’ll find 40 to 50 different soil types in every county,” Williamson said. “Using aerial photography, we record where the different soils occur on the land. Then we take all the information, send samples to the laboratory or test it locally. We analyze how much sand or clay is in the soil, also the amount of lime and the pH, or acidity, of the soil,” he added.

As they walked or drove vast expanses of the state, soil scientists described and sampled soils, then sent them to the Texas A&M University and Texas Tech University Soil Laboratories as well as the NRCS National Soil Survey Laboratory for further analysis.

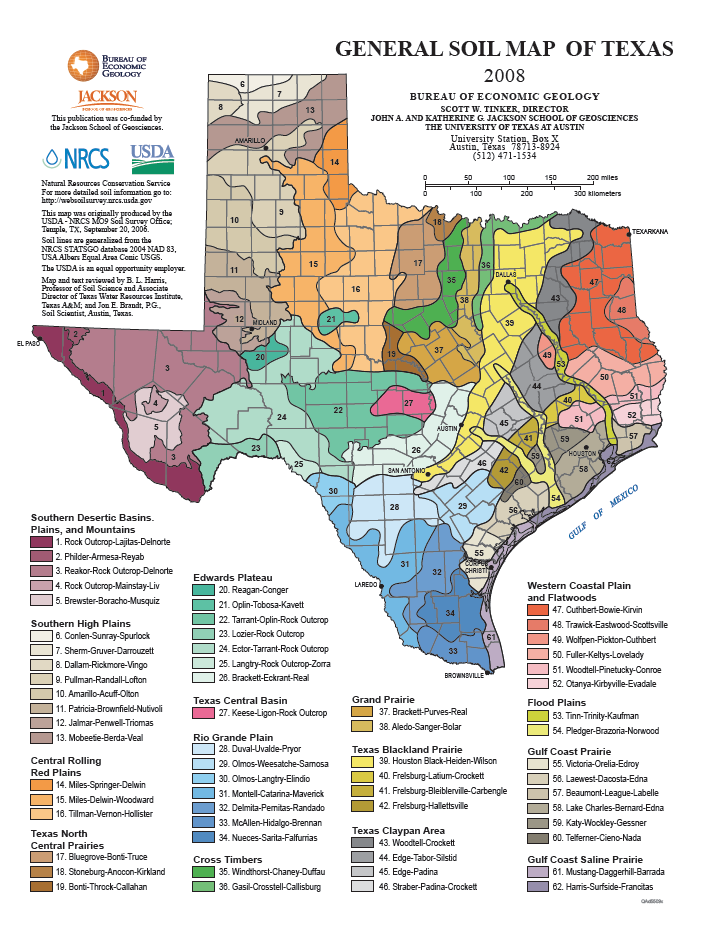

Once those analyses are finished, soil scientists draw conclusions from the results found in the test site, creating a crazy quilt of polygons and swirling shapes across the map’s terrain. This aggregate yields a mother lode of information.

“We can determine soil capability for septic tank systems or building homes. These maps are helpful to determine the best location for roads or buildings, planting gardens or deciding what type of crops to plant and how productive the land will be. Ranchers use the maps to decide how many head of cattle they can run on their acreage, depending on the soils productivity,” Williamson said.

“The soil resource is worth billions and billions of dollars. In recent years, maps have been digitized and put on the web where everyone has free access. Think how important soil resources are! This year alone, Texas soil produced $25 billion in agricultural products,” Williamson said.

Pingback: Ju-lyin with more Ollas - Doug.Land